The greenest building is the one that already exists; its upfront carbon cost has already been paid.

- New “Net Zero” homes focus on future operational savings but often start with a massive, hidden “carbon debt” from new materials and construction.

- Thoughtful renovation and material salvage drastically reduce a home’s total lifecycle emissions, making it a superior environmental choice.

Recommendation: Before choosing new construction, always calculate the embodied carbon cost. Prioritizing a deep energy retrofit of an existing structure is the most impactful step towards conscious building in Canada.

For environmentally conscious homebuyers in Canada, the term “Net Zero” has become the gold standard. It promises a future of minimal energy bills and a light environmental footprint. We’re told that advanced technology, superior insulation, and on-site energy generation make a new-build the pinnacle of green living. But this narrative overlooks a colossal, inconvenient truth: the carbon cost of construction itself.

This hidden impact is called embodied carbon—the sum of all greenhouse gas emissions released during the extraction, manufacturing, transportation, and assembly of building materials. A new Net Zero home, with its tons of fresh concrete, new steel, and imported finishes, starts its life with a massive carbon debt. Before it saves a single kilowatt of energy, it has already contributed significantly to atmospheric carbon.

What if the truly radical, more effective green strategy wasn’t to build anew, but to honour and upgrade what’s already standing? This article reframes the debate. We will move beyond the alluring promise of operational efficiency to uncover the profound environmental benefits of renovation. By analyzing material choices, deconstruction techniques, and the long-term value of existing structures, we will demonstrate why retrofitting is often the most responsible, sustainable, and intelligent path forward.

This guide provides a lifecycle consultant’s perspective on making a truly green housing choice in Canada. We will explore the carbon impact of core materials, the smart way to dismantle rather than demolish, and how to see through marketing claims to make an informed decision that benefits both your portfolio and the planet.

Summary: Why Renovating an Existing Building is a Smarter Green Choice than a New Build

- Why choosing mass timber over concrete reduces the building’s carbon footprint?

- How to deconstruct a kitchen rather than demolishing it to save carbon?

- Quarry distance: why buying local stone matters for your carbon score?

- How to spot “eco-friendly” marketing that ignores embodied energy?

- Why building it right the first time is the ultimate carbon strategy?

- Why tearing out horsehair plaster destroys the soundproofing of old homes

- What is the difference between “Ready” and “Certified” and which should you pay for?

- How will the upcoming 2030 Net Zero building codes impact the resale value of homes built today?

Why choosing mass timber over concrete reduces the building’s carbon footprint?

The conversation about embodied carbon starts with the structural skeleton of a house. For decades, concrete and steel have been the default choices for their strength and perceived durability. However, they are incredibly carbon-intensive to produce. The manufacturing of cement, the key ingredient in concrete, is responsible for approximately 8% of global CO2 emissions alone. This creates a massive upfront carbon debt for any new building.

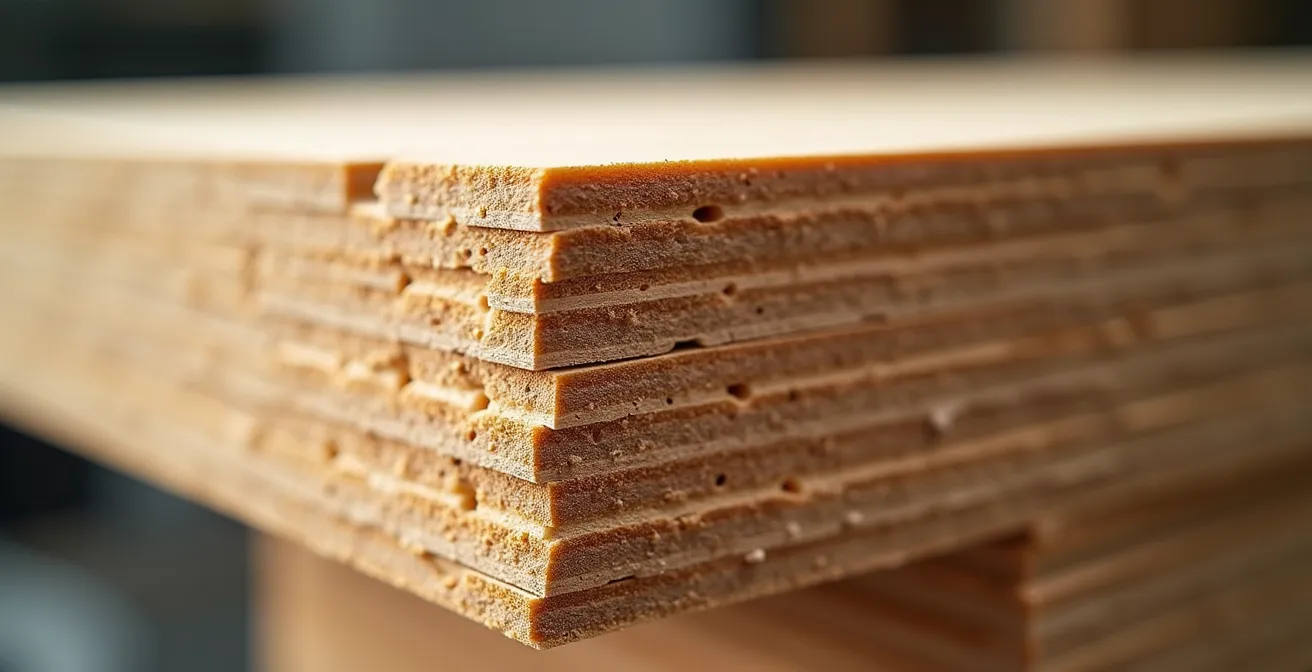

Mass timber, particularly products like Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT), offers a powerful alternative. Timber is a renewable resource that actively sequesters carbon as it grows. A tree absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere, and that carbon remains locked within the wood when it is harvested and used in a building. Instead of emitting carbon, the building’s very structure becomes a stable, long-term carbon sink. Research from leading institutions confirms the benefits; according to an MIT analysis, mass timber buildings can lower embodied carbon emissions by up to 40% compared to traditional concrete and steel structures.

Canadian projects are already proving the viability of this approach. The University of Toronto’s Academic Wood Tower, for instance, was redesigned from a concrete plan to a mass timber one, significantly cutting its carbon footprint and construction time. This shift highlights a fundamental principle of lifecycle accounting: the material choices made on day one have a more significant and immediate climate impact than decades of operational energy savings. By opting for a material that stores carbon instead of one that emits it, you are starting your project with a carbon credit, not a debt.

How to deconstruct a kitchen rather than demolishing it to save carbon?

The carbon-conscious mindset extends beyond structural materials to the process of renovation itself. The standard approach—demolition—is a carbon catastrophe. It sends tons of manufactured goods to the landfill, wasting the embodied energy used to create them and requiring new energy to produce their replacements. A kitchen renovation, for example, often involves smashing perfectly good cabinets, countertops, and appliances into a dumpster. Deconstruction is the strategic alternative: a careful, surgical process of dismantling a space to salvage materials for reuse.

Instead of a sledgehammer, deconstruction uses a screwdriver. Cabinets are unscrewed from the walls, preserving their integrity. Stone countertops are carefully removed so they can be recut for another project. Appliances, fixtures, and even flooring can be donated or resold. This approach has a dual benefit: it prevents landfill waste and, more importantly, avoids the carbon emissions associated with manufacturing new products. Every cabinet box saved is a cabinet box that doesn’t need to be built, packaged, and shipped from a factory.

Organizations across Canada, like Habitat for Humanity’s ReStore, have streamlined this process. They partner with renovators to appraise and remove materials, providing a tax receipt for the donation and ensuring the items find a new home. This transforms what was once considered “waste” into a valuable community resource. Implementing a deconstruction plan is a tangible way to drastically lower the embodied carbon of your renovation project.

Your 5-Step Canadian Kitchen Deconstruction Plan

- Appraisal First: Schedule a pre-demolition appraisal with organizations like Habitat for Humanity ReStore. This determines what can be salvaged and provides documentation for tax-deductible donation receipts.

- Safe Utility Disconnection: Hire certified professionals for gas and electrical work. Ensure water lines are properly capped to prevent damage. Safety is non-negotiable.

- Intact Cabinet Removal: Use a drill to carefully unscrew cabinets from walls. Keep doors and hardware attached, and use moving blankets to protect the finish during transport.

- Careful Countertop Disassembly: Stone (granite, quartz) and solid wood surfaces have high resale value. Work with professionals to remove them without cracking, allowing them to be recut for new installations or furniture.

- Strategic Material Sorting: Create dedicated piles for different destinations: metal components for local scrap recyclers, salvaged cabinets and appliances for ReStore, and only true waste for the landfill bin.

Quarry distance: why buying local stone matters for your carbon score?

Once you’ve salvaged what you can, the next step is selecting new materials. Here again, the focus must be on embodied carbon, and a major component of that is transportation. A heavy material like natural stone, if quarried in another continent, transported to a port, shipped across an ocean, and then trucked to your home, carries a staggering carbon footprint from fuel alone. This is the concept of material provenance—understanding not just what a material is, but where it comes from and how it got to you.

Canada has a rich supply of beautiful, durable stone, from Tyndall Stone in Manitoba to Stanstead Granite in Quebec and slate in British Columbia. Choosing a local or regional stone over an import from Italy or Brazil can drastically reduce the transportation portion of its embodied carbon. The difference is not trivial; using rail and truck transport from a domestic quarry is vastly more efficient than a multi-modal international journey.

This comparative analysis shows how sourcing stone within Canada significantly reduces carbon impact compared to popular imported options. While the initial material cost might be similar, the environmental cost is far lower when you factor in the reduced “carbon miles.”

| Canadian Stone Type | Source Region | Typical Transport Method | Carbon Impact vs. Import |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tyndall Stone | Manitoba | Rail (CP/CN) | 60% lower than US imports |

| Stanstead Granite | Quebec | Rail + Truck | 45% lower than overseas |

| BC Slate | British Columbia | Truck (regional) | 70% lower than imports |

Asking “where is this from?” is as important as asking “how much does it cost?”. Prioritizing local materials is a powerful lever for reducing the hidden carbon debt of your project. This principle applies not just to stone, but to lumber, fixtures, and finishes as well.

How to spot “eco-friendly” marketing that ignores embodied energy?

The term “eco-friendly” has become a powerful but often misleading marketing tool. Many products are promoted for their energy-saving features during use (operational carbon) while completely ignoring the massive carbon footprint of their creation (embodied carbon). This is a form of greenwashing designed to make you feel good about a purchase without providing the full picture. As a conscious buyer, you need to become a discerning detective.

The most common tactic is focusing exclusively on R-value for insulation or Energy Star ratings for windows. While important, these metrics say nothing about the carbon emitted to produce the fibreglass, foam, or vinyl in the first place. A truly green product must have its entire lifecycle assessed. In Canada, the International Institute for Sustainable Development reports that buildings represent 18% of national emissions, a figure that includes both operational and embodied carbon. Ignoring the latter means ignoring a huge piece of the puzzle.

To cut through the noise, you must demand transparency. Legitimate sustainable products are backed by data, not just vague claims. Look for an Environmental Product Declaration (EPD), which is like a nutritional label for a product’s environmental impact, including its embodied carbon. Furthermore, rely on established, third-party Canadian certifications like LEED Canada, Built Green Canada, or the CHBA Net Zero Home Labelling Program. These programs evaluate a project holistically, not just on one or two features.

Your Checklist for Detecting Greenwashing in Canada

- Demand the EPD: Ask for the Environmental Product Declaration. If a manufacturer claims their product is “green” but cannot provide transparent lifecycle data, be skeptical.

- Look for Recognized Certifications: Prioritize products and builders recognized by LEED Canada, Built Green Canada, or the CHBA Net Zero program. These logos signify third-party verification.

- Question Operational-Only Claims: If marketing material only boasts about future energy savings (“lowers your bill!”), ask directly: “What is the embodied carbon cost of this product/project?”

- Calculate the Carbon Payback: For a new feature, determine how many years of operational energy savings it will take to “pay back” the carbon emissions required to produce it. Sometimes, the payback period is longer than the product’s lifespan.

- Verify Full Carbon Accounting: For wood products, check if the EPD includes impacts from land use changes and forestry. This can add up to 72% to the total lifecycle emissions if not managed sustainably.

Why building it right the first time is the ultimate carbon strategy?

The most profound way to minimize a home’s lifetime carbon footprint is through durability. Every product that fails prematurely—a leaky window, a cracked foundation, a peeling roof—must be replaced. This replacement triggers a new cycle of manufacturing, transportation, and installation, adding more embodied carbon to the building’s tally. The greenest material is one you only have to install once. Therefore, renovating an existing home with high-quality, durable materials is an exceptionally powerful carbon-saving strategy.

Case Study: The Calgary Net Zero Renovation

Peter Darlington’s transformation of his 1985 Calgary home into Canada’s first certified CHBA Net Zero Energy renovation is a masterclass in durability. Instead of demolishing, he chose to super-insulate the existing structure with materials like expanded polystyrene, which is 100% recyclable and has minimal embodied carbon. All new systems were specifically chosen to withstand harsh Canadian climate cycles, from freeze-thaw to heavy snow loads. The project prevents an estimated 13 tonnes of CO2 emissions annually. The key takeaway is that the renovation was designed *not* to be redone in a decade, avoiding future cycles of embodied carbon and saving an estimated $5,000 per year in energy costs.

This principle challenges the “fast and cheap” renovation culture. It means investing in better windows that won’t lose their seal, using robust siding that can handle hail, and ensuring flashing details are executed flawlessly to prevent water ingress. It’s a shift from short-term cost-saving to long-term lifecycle value. While a more durable material might have a higher initial price, its total cost—both financial and environmental—is far lower when you factor in a lifespan of 50 years instead of 15.

Furthermore, sustainable forestry practices ensure that even the source of materials like timber can be a net positive. As Robert Mendelsohn, a leading expert at the Yale School of the Environment, notes:

Modern timber harvesting is based on purpose-grown forests. If demand rises, more forests are planted — and that leads to more carbon being stored, not less.

– Robert Mendelsohn, Edwin Weyerhaeuser Davis Professor Emeritus of Forest Policy, Yale School of the Environment

Choosing high-quality, sustainably sourced materials and installing them correctly ensures the carbon sequestered in your home stays there for generations.

Why tearing out horsehair plaster destroys the soundproofing of old homes

A common impulse in renovating older Canadian homes is to gut the interior down to the studs, replacing old lath and plaster walls with modern drywall. This is often seen as a step towards modernization, but it frequently destroys one of the most valuable and overlooked features of an old home: its superior acoustic performance. The mass and density of traditional horsehair plaster provide a level of soundproofing that is difficult and expensive to replicate with modern materials.

Lath and plaster is a system built in layers: wooden lath strips are nailed to the studs, followed by a “scratch coat,” a “brown coat,” and a final smooth finish coat of plaster. This composite structure is thick, irregular, and dense, making it excellent at blocking airborne sound. By contrast, a standard sheet of drywall is a relatively thin, uniform panel that vibrates more easily, allowing sound to pass through. In fact, traditional lath and plaster walls typically achieve Sound Transmission Class (STC) ratings that are 15 to 20 points higher than a basic drywall assembly.

Tearing out this high-performance, existing material and sending it to the landfill only to replace it with a lower-performing, new material is the antithesis of sustainable renovation. It wastes the significant embodied carbon of the original plaster and requires new manufacturing emissions for the drywall. The smarter, greener, and often quieter approach is to repair, not replace. Most cracks and damage in old plaster can be expertly repaired using modern techniques like plaster washers and mesh tape, preserving the wall’s acoustic integrity and historic character.

This is especially critical in semi-detached homes or row houses common in cities like Toronto and Montreal, where acoustic privacy between units is paramount. Preserving the original plaster in a party wall is the single best way to maintain peace and quiet. Before reaching for the sledgehammer, consider the hidden value you’re about to destroy.

What is the difference between “Ready” and “Certified” and which should you pay for?

As you navigate the world of green building in Canada, you will frequently encounter two terms: “Net Zero Ready” and “Net Zero Certified.” While they sound similar, the difference between them is crucial for both your home’s performance and its financial value. Understanding this distinction is key to avoiding a form of sophisticated greenwashing.

A Net Zero Ready home is essentially a promise. It has been designed and built with higher levels of insulation and airtightness, and includes the necessary infrastructure (like conduit and structural capacity) to add a renewable energy system, such as solar panels, in the future. However, it does not actually generate its own energy, and its performance has not been verified by a third party after construction.

A Net Zero Certified home, in contrast, is a proven performer. It has the renewable energy system installed and operational. More importantly, its actual energy performance has been tested and verified by a third-party expert under a program like the one administered by the Canadian Home Builders’ Association (CHBA). This certification proves that the home performs as designed, producing as much clean energy as it consumes over a year.

From a financial perspective, the “Certified” label carries far more weight. It unlocks access to green financing products from major Canadian banks and makes you eligible for significant rebates. For example, the CMHC provides a mortgage insurance premium rebate of up to 25% for homes that meet high energy-efficiency standards, a benefit typically reserved for certified properties. The table below outlines the key differences:

| Aspect | Net Zero Ready | Net Zero Certified |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Design promise, solar-ready infrastructure | Third-party verified performance |

| Canada Greener Homes Grant | Not eligible for full rebate | Eligible for up to $5,000 |

| Green Mortgage Rates | Limited access | Full preferential rates from major banks |

| Resale Value Impact | Moderate increase | Higher, defensible premium |

| EnerGuide Rating Required | Initial only | Post-retrofit evaluation mandatory |

While “Ready” is a step in the right direction, paying the premium for “Certified” provides a verifiable asset with tangible financial returns and the assurance of real-world performance.

Key Takeaways

- Embodied carbon is critical: The carbon footprint of materials and construction is a massive, immediate environmental cost that Net Zero operational savings may never repay.

- Renovate first: The greenest building is the one that already exists. A deep energy retrofit avoids the huge carbon debt of a new build.

- Provenance matters: Choosing local, durable, and salvaged materials drastically reduces a project’s total lifecycle carbon impact.

- Demand verification: Look past “eco-friendly” marketing. Rely on EPDs and recognized Canadian certifications like CHBA Net Zero Certified to ensure true performance.

How will the upcoming 2030 Net Zero building codes impact the resale value of homes built today?

Making a housing choice today isn’t just about current standards; it’s about anticipating the future. The Canadian government is aggressively moving towards a greener building stock, with a national model code that aims for all new constructions to be “Net Zero Energy Ready” by 2030. This means that within a few short years, the baseline for new homes will be drastically higher than it is today.

According to Natural Resources Canada, these 2030-compliant buildings will be up to 80% more efficient than those built to current minimum codes. This creates a significant financial risk for anyone buying or building a “standard” home in 2024. When the 2030 codes become the norm, a home built to today’s basic standards will be functionally obsolete, facing a steep value depreciation. Its energy performance will be visibly inferior, and bringing it up to the new standard will be a costly undertaking.

This is where deep renovation of an existing home becomes a powerful strategy for future-proofing your investment. By retrofitting an older home to meet or exceed the upcoming Net Zero Ready standards, you are not just saving an existing structure from landfill; you are elevating it to the top tier of the future housing market. Its performance will be comparable to a brand-new 2030 home, but without the massive embodied carbon debt.

Pilot programs like Edmonton’s mandatory energy labeling for homes for sale signal what’s to come. Soon, an EnerGuide rating will be as standard on an MLS listing as fuel economy is on a car. In that transparent market, a deeply retrofitted older home with proven low energy consumption and low embodied carbon will be a premium asset. Conversely, a new build from 2024 that just met the minimum code will be at a distinct disadvantage, its value immediately challenged by the higher-performing inventory built just a few years later.

The logical next step for any prospective homeowner or renovator is to move from theory to practice. Begin by commissioning an EnerGuide evaluation for your existing or target property to establish a performance baseline, and consult with a building professional certified in lifecycle assessment to analyze the embodied carbon of your plans. This proactive analysis is the foundation of a truly sustainable and valuable real estate investment.